By Nick McKenzie and David Marin-Guzman

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

On October 5, underworld figure Mick Gatto offered an unsolicited proposition to veteran Melbourne architect Joseph Toscano.

Toscano was told he could sit down with the underworld figure to resolve the architect’s commercial dispute with building company Cobolt Constructions, which Gatto claimed to be representing.

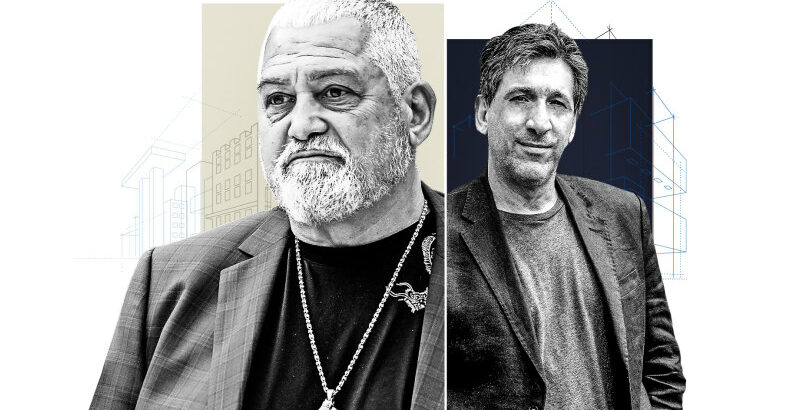

Joseph Toscano.

But if Toscano wasn’t interested in this meeting, he could face trouble caused by the man infamously caught up in Melbourne’s gangland wars.

“We can cause you grief,” Gatto told Toscano. “And I know you have enough grief in your life already.”

Gatto hinted he was capable of preventing other building companies from completing Toscano’s Melbourne inner-city apartment block development.

“I can stop anyone doing anything, mate. And I say that respectfully, I don’t want to be a smarty,” he says in a record of the conversation.

It is often reported that Gatto is the last man standing from Melbourne’s bloody gangland wars, but it is less well known he is still going strong in the face of repeated attempts from various authorities to curb his ubiquitous role in the construction industry.

Gatto has long cast a shadow over Melbourne’s construction industry as a self-styled “mediator and arbitrator”, making the occasional entry into the NSW sector as well.

Mick Gatto in June 2022.Credit: Quinn Rooney

The fact he is still operating, along with the rare glimpse of how he plies his trade, illustrates how certain construction industry power structures have not only withstood repeated attempts at reform but continue to flourish.

According to Gatto, building companies call on him to sort out contractual or industrial disputes, while the construction union assists him.

“I have got friends there [in the union] and they support me if things are done the right way,” Gatto explained when asked last week about his intervention in Toscano’s development dispute.

“There are plenty of people around like me who deal with the union and consult, but they are not as high-profile as me… they do it under the radar.”

For 20 years, Coalition governments, commissions of inquiry, police taskforces and regulators have tried to bring Gatto undone. The hulking, grey haired ex-boxer has outlasted all of them.

The 2002 Cole royal commission exposed Gatto’s role as an industry fixer (the commission aired allegations Gatto was either a standover man or an “industrial consultant”).

That Coalition government-ordered commission led to the establishment of the Australian Building and Construction Commission, which the Albanese government abolished in February.

Anecdotally at least, problems are brewing in both Sydney and Melbourne. This masthead has spoken to a dozen industry and union insiders who describe how bikie gangs and Italian and Middle Eastern underworld figures are quietly entrenching themselves in the industry at a scale not seen in years. They would not speak openly over concern about the impact on their professional interests.

“It’s worse now than ever,” says one former union official who insists that when he served at the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union’s construction arm, the union saw its role as keeping crooks at bay, at least ensuring they didn’t rip off workers or compromise safety.

A former Building and Construction Commission official scoffs at this suggestion: “Gatto works hand in glove with some in the union. He couldn’t exist without their support.”

Still, it is building companies, not unions, that pay his fees, which can range from $50,000 to $1 million per dispute resolution, depending on the client and complexity of the issue.

Gatto told one developer recently that he mediates 10 construction industry disputes a week.

If Gatto is, as he insists, simply the most high-profile of a small army of industrial relations fixers, it raises old questions about an industry crucial to solving the housing crisis and delivering vital infrastructure projects.

Mick Gatto at Shane Warne’s memorial service in March.Credit: Getty Images

Business records and sources reveal colourful industry players are working on federal or state government projects or have moved into Indigenous labour hire, which makes it easier for them to win contracts due to governments’ social procurement rules.

Gatto is linked to labour hire entity M Group, which set up Indigenous firm Jarrah as part of a joint venture and has won work on several large Victorian projects with CFMEU backing.

Gatto’s company Arbitration and Mediation Services was an original shareholder of the group before transferring those shares to his daughter.

Gatto is also paid to sort out the firm’s union issues and has a CFMEU-endorsed industrial agreement, which is a de facto requirement for scoring work on CBD projects.

One of the reasons involvement of underworld figures in the construction industry remains hard to quantify and dissect is because so few working within the sector are willing to go on the record. Joseph Toscano is a rare exception.

Having weathered COVID lockdowns that removed his initial choice of firm, the veteran architect contracted Cobolt Constructions in 2021 to build a 10-storey apartment building in the inner-Melbourne suburb of Collingwood.

Their relationship soured over cost, time and quality issues, finally becoming irreparable in January.

The development site in Wellington Street, Collingwood.Credit: Penny Stephens

The question of who is to blame for this breakdown is mired in claim and counter-claim. Toscano and Cobolt’s Christian Munn both called in lawyers after Munn suspended his company’s services, leaving Toscano with a long list of complaints about Cobolt’s performance and scrambling for a new builder.

Munn has accused Toscano’s firm of acting unfairly and of owing Cobolt significant funds and materials.

What is undisputed is that in early October, Gatto, and his business partner John Khoury, arrived on the scene.

Gatto called Toscano twice, explaining on both occasions that he was “ringing on behalf of Cobolt” and reciting some of the same contested complaints made separately by Munn (who claims to know nothing of Gatto’s involvement).

If you are not interested, we will go away and whatever happens happens.

“We are trying to rectify these issues before they get stretched out along the way with lawyers and all that,” Gatto told Toscano, according to a record of the conversation.

Communicating with a gruff politeness, Gatto warned Toscano he could cause him “grief” and claimed he was capable of “stopping” the site’s completion, while mentioning the name of the building company that Toscano hoped would finish his development.

According to a record of the conversation, Gatto also mentioned he had the union onside and that these connections could help get his development restarted.

Cobolt is a non-union-endorsed company that has been a target of the CFMEU over purported safety issues on its sites, while the company that is Toscano’s preferred replacement has a union-endorsed employee agreement.

“We just want to sit down and have a chat and find a common denominator. If you are interested. And if you are not interested, we will go away and whatever happens happens,” Gatto told Toscano.

A day after this call, on October 6, Gatto’s business partner Khoury arrived at Toscano’s site, seeking entry and the recovery of site materials that Cobolt claims are owned by it or its subcontractors.

Khoury provided the security guard with his business card and left without incident.

Khoury is a mostly genial businessman who has avoided the same fearsome reputation as Gatto but is a fixture of the old Carlton Crew.

The crew is a grouping of underworld figures who rose to prominence during the gangland wars between 1996 and 2011, a period in which several of Gatto’s closest underworld friends were murdered and he shot dead hitman Andrew Veniamin in an act a jury accepted was self-defence.

Gatto despises public discussion of his underworld history, promoting himself as a grandfather devoted to charity (one of his grandchildren has autism and Gatto is devoted to fundraising for the cause).

In an at times testy interview, Gatto acknowledged he is called on in the construction industry because his reputation precedes him.

Asked why Cobolt or one of its subcontractors would hire him, Gatto explained: “Because they have tried every other way. They have tried legally, they have tried talking to him [Toscano], they know that I’ve got a reputation in the industry like you said I had. And they call on me hoping that I can talk some sense into these people. You know the way it works.

“We don’t stand over anyone. We don’t belt anyone. We don’t do the wrong thing by anyone. Fair enough, everyone ends up with a bad taste in their mouth, but we try to resolve things, quickly and amicably.”

Since the interaction with Gatto, Toscano’s efforts to restart his development have stalled, with builders privately claiming they have been warned off the job by unnamed figures in the CFMEU until the dispute is resolved.

A CFMEU spokesperson did not respond to questions. Toscano’s son, Nick, an energy reporter with The Age and Sydney Morning Herald, advised his father to contact police about Gatto’s approach, but while detectives were sympathetic, there is no evidence of illegality by Gatto or Khoury (Nick Toscano had no role in the preparation of this story).

Joseph Toscano believes that putting his experience into the open might help change his industry.

“It is scandalous that the building industry operates this way. It is not an environment for anyone to do business in. There are faceless men who have nothing to do with the business at hand who intervene in disputes … it is galling.”

When called by this masthead, Cobolt’s Munn claimed it was Toscano’s conduct as developer that was the problem and insisted he had no knowledge of Gatto’s involvement or why he was claiming to be working for Cobolt.

Munn suggested an errant subcontractor may be responsible for hiring the colourful mediator, but refused to say who.

Gatto denied he had the power to affect Toscano’s apartment project.

“I can’t shut down a site in the city,” he said.

The power to stop building works, Gatto insists, resides only with the union, and he says it is only exercised when workers are being ripped off.

Union politics aside, while there are building firms prepared to pay him, Gatto is going nowhere.

“Print the truth, I have no issue with you,” he told this masthead, insisting his was a brief and uneventful interjection into Toscano’s building project.

“If you don’t print the truth, I have got a problem with you. And if I ever see you, I will deal with you.”

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article